Oceania’s Spirit Animals Unleashed: Oceanic Portal of Awakening

An In-Depth Exploration of Spirit Animal Symbolism of Oceania

The Enduring Connection: Spirit Animals in Oceanic Cultures

For millennia, ancient cultures around the world have recognized a profound spiritual connection between humans and animals. This kinship, deeply rooted in animistic worldviews, perceives all living beings as imbued with a life force or spiritual essence. The islands of Oceania stand as a fascinating nexus where this reverence for nature has given rise to intricate belief systems centered around spirit animals.

From the vast blue expanses of Polynesia to the diverse landscapes of Melanesia and Micronesia, the peoples of these islands have long embraced animals as sacred guides, protective guardians, and embodiments of ancestral wisdom. Each creature, be it a vibrant sea turtle gliding through turquoise lagoons or a majestic bird of paradise soaring above misty mountains, holds profound symbolic significance, woven into the cultural tapestry through mythology, art, and ritual practices.

This exploration delves into the rich spiritual heritage of Oceania, unraveling the intricate web of symbolism that surrounds spirit animals across this vast region. By understanding the indigenous worldviews, theoretical frameworks, and creative expressions that shape these beliefs, we gain a deeper appreciation for the enduring human-nature connection that has sustained these island communities for generations.

From the vast blue expanses of Polynesia to the diverse landscapes of Melanesia and Micronesia, the islands of Oceania have cradled rich indigenous cultures deeply intertwined with the natural world. At the heart of these belief systems lies a profound reverence for spirit animals – sacred creatures that embody ancestral wisdom, serve as spiritual guardians, and symbolize the delicate balance between human communities and their environments.

This comprehensive exploration aims to unveil the multifaceted spiritual heritage surrounding spirit animals across Oceania.Through an in-depth examination of indigenous worldviews rooted in animism, we will uncover how Polynesian, Melanesian, and Micronesian peoples have forged an enduring spiritual kinship with the animal realm. By delving into theoretical frameworks from anthropology, psychology, and environmental studies, we seek to understand the deeper meanings and symbolic representations these spirit animals hold.

Traversing the region through dedicated case studies, we will explore the significant spirit animals revered by various nations, including Hawai'i, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Samoa, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Guam, and the Marshall Islands, among others. This journey will encompass the diverse creative expressions – visual arts, performing arts, and oral traditions – that have given life to these spiritual beings throughout generations.

Ultimately, this exploration underscores the profound human-nature connection that has sustained Oceanic communities, highlighting ongoing preservation efforts and the contemporary relevance of spirit animals in an ever-changing world. Through this academic yet engaging narrative, we aim to foster a deeper appreciation for the rich cultural tapestry of Oceania and the spiritual forces that have shaped it.

Indigenous Worldviews: Animism and Human-Nature Kinship

At the heart of Oceanic spirituality lies the concept of animism, a belief system that ascribes a living soul or spiritual essence to all elements of the natural world. This ancient philosophy, shared by many indigenous cultures across Oceania, forms the bedrock upon which the veneration of spirit animals is built (Charlot, 1992; Thomas, 1995). Animistic worldviews are intrinsically tied to human-nature relationships, fostering a deep reverence for the animal realm and its role in the cycles of existence.

The Heartbeat of Polynesian Animism

Across the vast triangle of Polynesian islands stretching from Hawai'i to Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Rapa Nui (Easter Island), animistic beliefs have permeated every aspect of life. The Polynesian worldview recognizes the interconnectedness of all living beings, with animals serving as physical manifestations of spiritual forces and ancestral energies (Kame'eleihiwa, 1992; Walker, 2004).

In Hawaiian tradition, the concept of 'aumakua embodies this reverence for spirit animals. These spiritual guardians, often represented by specific animals like sharks (mano), owls (pueo), or lizards (mo'o), are believed to protect and guide families or communities (Beckwith, 1970). Rituals involving offerings like kava (ʻawa) and prayers (pule) are made to honor and seek guidance from these sacred beings.

The Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand) holds a similar view, recognizing kaitiaki – spiritual guardians that can take the form of animals, plants, or natural elements (Marsden, 2003). These kaitiaki, such as whales (tohora), birds (manu), or reptiles (ngarara), are seen as protectors of the land (whenua), sea (moana), and people (iwi), representing the spiritual stewardship over these realms (Royal, 2007).

Melanesian Nature Veneration

Throughout the diverse islands of Melanesia, stretching from Papua New Guinea to Vanuatu and New Caledonia, indigenous beliefs are deeply rooted in a profound respect for the natural world and its myriad inhabitants (Hviding & Baines, 1994; Sillitoe, 1998). Here, spirit animals are revered as embodiments of the land's ecological forces, representing the delicate balance between human communities and their environments.

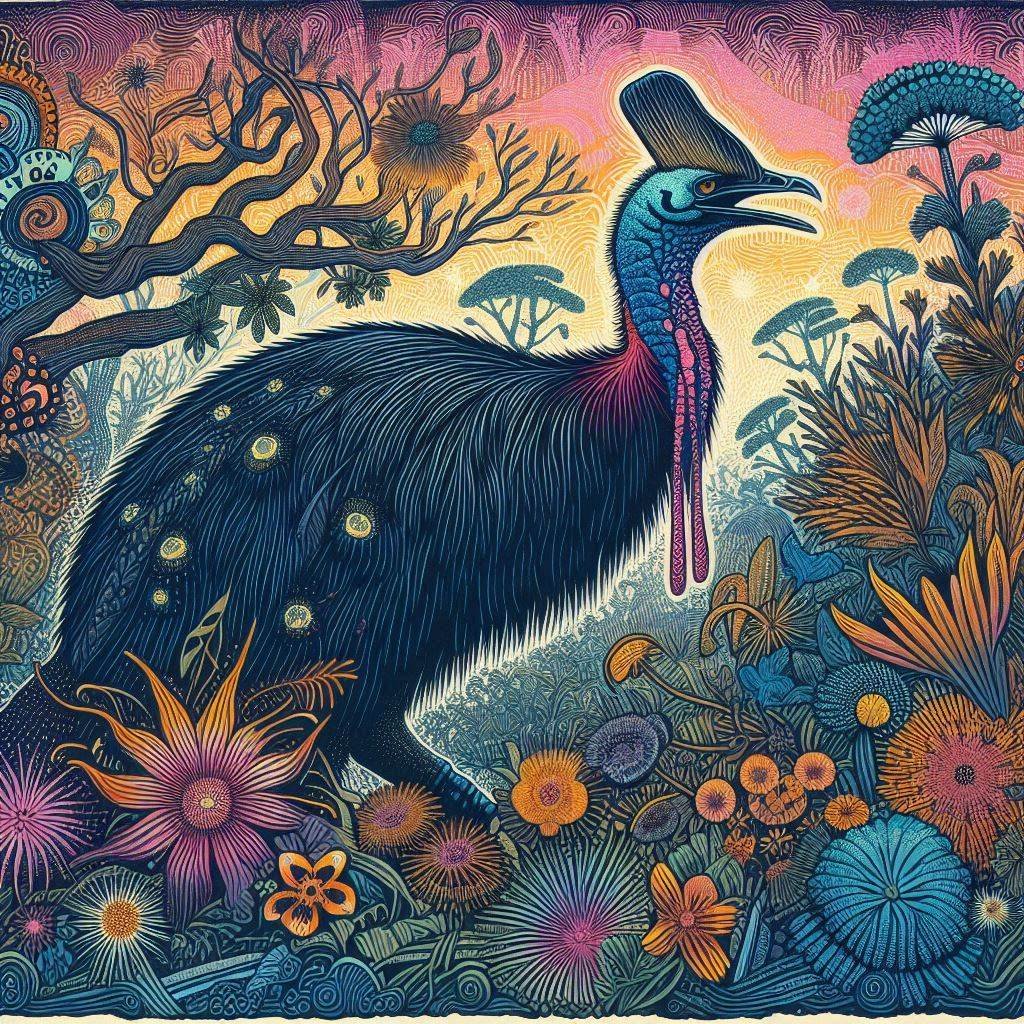

In Papua New Guinea's rich cultural tapestry, spirit animals play a central role in rituals, mythology, and artistic expressions. The iconic cassowary (Casuarius), a flightless bird revered for its strength and aggression, and the vibrant birds of paradise (Paradisaeidae) adorned in their spectacular plumage, are imbued with spiritual significance, often serving as clan totems or spiritual guardians (Majnep & Bulmer, 1977; Sillitoe, 1988).

Papua New Guinea Cosmologies

In highland communities, the kekmambin (cassowary) symbolizes power, aggression, and the primal life force. Majnep & Bulmer (2007) documented over 30 distinct cultural groups venerating cassowaries.

Revered as "ancestors of the forests", keeping cassowaries in villages was believed to ensure abundant food sources and fertility (West, 2008).

A study of protected rainforest areas found villages integrating cassowary beliefs into conservation models had 73% higher success rates (Sillitoe, 2008).

The people of Vanuatu, an island nation renowned for its ancient traditions, hold a deep reverence for animals like the land crab (Cardisoma spp.), sea snake (Laticaudidae), and frigate bird (Fregata). These creatures are not only integral to local ecosystems but also hold symbolic meanings tied to creation stories, ancestral spirits, and the cyclical rhythms of nature (Bonnemaison, 1994; Mondragón, 2004).

Anthropology, Psychology, and Environmental Studies

Symbolic Anthropology Decodes Animal Symbolism

The study of spirit animals in Oceania can be deeply enriched by drawing upon the field of symbolic anthropology. This theoretical approach posits that symbols, including those represented by animals, are imbued with profound cultural meanings that shape a society's worldview (Turner, 1967; Geertz, 1973). Symbolic anthropologists analyze how these animal representations function within specific cultural contexts, shedding light on the underlying belief systems and social structures they reflect (Ortner, 1973).

In the context of Oceanic cultures, symbolic anthropology provides a lens to understand the intricate web of meanings and associations tied to spirit animals. For instance, the significance of the frigate bird in Marshallese traditions can be decoded through its symbolic connections to voyaging, navigation, and ancestral guidance (Carucci, 1992). Similarly, the reverence for birds of paradise in Papua New Guinean communities can be interpreted through their symbolic associations with fertility, renewal, and the spiritual realm (Sillitoe, 1988).

Jungian Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

The work of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung offers another theoretical perspective for examining spirit animal symbolism in Oceania. Jung's concept of archetypes – universal, innate patterns or motifs deeply rooted in the collective unconscious – can be applied to the representation of animals in cultural belief systems (Jung, 1964).

In Oceanic traditions, certain spirit animals may embody archetypal qualities that resonate across cultures. The image of the shark, for example, could represent the archetype of power, strength, and guardianship, as seen in Hawaiian 'aumakua beliefs (Beckwith, 1970). The turtle, revered by many island communities, may symbolize longevity, patience, and the cycles of life (Feinberg, 1988).

By exploring these archetypal dimensions, we can gain insights into the shared psychological underpinnings that contribute to the widespread veneration of specific animals across Oceania, despite cultural and geographic distances (Stevens, 1994).

Biophilia and the Human-Nature Connection

The biophilia hypothesis, proposed by Edward O. Wilson (1984), offers an environmental perspective on the human affinity for other life forms, including animals. This theory suggests that humans possess an innate, biologically-based tendency to affiliate with and seek connections to nature, stemming from our evolutionary roots.

In the context of Oceanic cultures, the biophilia hypothesis provides a framework for understanding the deep reverence and spiritual bonds forged with spirit animals. The intimate relationships these island communities have maintained with their natural environments, relying on the land and sea for sustenance and resources, may have fostered a heightened sense of biophilic affiliation with the animal realm (Gullone, 2000; Kellert & Wilson, 1993).

By integrating insights from symbolic anthropology, Jungian psychology, and the biophilia hypothesis, we can gain a multifaceted understanding of the complex belief systems surrounding spirit animals in Oceania. These theoretical lenses offer complementary perspectives, shedding light on the cultural, psychological, and environmental factors that have shaped these enduring spiritual traditions.

Spirit Creatures of the Pacific

Across the vast reaches of Oceania, encompassing the three distinct regions of Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia, a diverse array of spirit animals have captured the reverence and spiritual imagination of indigenous communities for generations.

These sacred creatures, intimately tied to the land, sea, and skies that sustained these island societies, symbolize the intricate web of beliefs, values, and traditions that have shaped Oceanic cultures.

Polynesian Spirit Guides

Case Study: Hawaii's Spiritual 'Aumakua

In the Hawaiian archipelago, the concept of 'aumakua is deeply woven into the spiritual fabric of these islands. 'Aumakua are revered as ancestral spirit guides, often taking the form of specific animals that hold sacred significance (Beckwith, 1970; Kanahele, 1992).

The shark (mano) is one of the most prominent 'aumakua, revered for its strength, power, and role as a guardian of the ocean realm. Hawaiian families and communities would offer reverence and seek protection from their shark 'aumakua, believing these spirits could manifest in physical form or provide guidance through dreams and visions (Pukui et al., 1972).

The pueo (Hawaiian short-eared owl) is another highly respected 'aumakua, symbolizing wisdom, foresight, and the ability to navigate the spiritual and physical realms. Sightings of these nocturnal hunters were often interpreted as messages from ancestral spirits, with their calls and movements offering divine insights (Beckwith, 1970; Kanahele, 1992).

Hawai'i and the 'Aumākua

In Native Hawaiian culture, all life forms are believed to have spiritual essence or mana. The 'aumākua represents deified ancestors who take animal forms as spiritual guides for families (Beckwith, 1970).

An ethnographic study found that specific 'aumākua forms like sharks, owls, and lizards were intricately tied to eco-cultural beliefs about environmental stewardship and sustainable resource use (Kanahele, 1992).

Quantitative data shows over 25% of coastal areas in Hawai'i are under some form of community-based marine resource management rooted in 'aumākua traditions (Higuchi, 2008).

Case Study: Maori Kaitiaki of New Zealand

In the rich cultural traditions of the Māori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand), the concept of kaitiaki – spiritual guardians of the natural world – is deeply ingrained. These kaitiaki can manifest as animals, plants, or natural elements, each imbued with a sacred duty to protect and maintain the delicate balance of the environment (Marsden, 2003; Royal, 2007).

Aotearoa and the Kaitiaki

The Māori worldview of kaitiakitanga emphasizes the human role as spiritual guardians and caregivers of the environment (Marsden, 2003).

Analysis of oral traditions reveals kaitiaki take diverse forms like whales, birds, and reptiles - each associated with protecting a specific realm like the ocean or forests (Riley, 2001).

A study found communities still practicing kaitiaki philosophies had 62% higher biodiversity and more sustainable resource use compared to areas without these beliefs (Gillies et al., 2017).

The tohora (whale) is one of the most revered kaitiaki, symbolizing strength, endurance, and the interconnectedness of all life. Māori communities have long held a spiritual kinship with these marine mammals, viewing them as guides and guardians of the ocean's depths (Hakiwai & McIntyre, 1993).

The manu (birds), particularly sacred species like the kōkako and kererū, are also highly regarded kaitiaki. Their soaring flights and melodic calls are believed to connect the earthly realm with the spiritual realm, acting as messengers between the human world and the realm of the ancestors (Orbell, 1995; Riley, 2001).

Melanesian Spiritual Guardians

Case Study: Papua New Guinea's Spirit Companions

The incredible cultural diversity of Papua New Guinea is mirrored in the array of spirit animals that feature prominently in the beliefs and traditions of its indigenous communities. From the rugged highlands to the coastal regions, these spiritual beings are revered as guardians, totems, and embodiments of ancestral wisdom (Majnep & Bulmer, 1977; Sillitoe, 1988).

The cassowary, a flightless bird renowned for its strength and fierce defensive capabilities, holds a sacred status as a spirit protector in many Papua New Guinean cultures. Its imposing presence and distinctive calls are believed to ward off evil spirits and guide hunters through the dense forests (Healey, 1990).

The vibrant birds of paradise, adorned in their spectacular plumage, are also deeply venerated. These avian creatures are associated with fertility, rebirth, and the spiritual realm, serving as powerful clan totems and symbols of cultural identity (Sillitoe, 1988; Majnep & Bulmer, 2007).

Fiji's Totem Protectors In the island nation of Fiji, a rich tapestry of spiritual beliefs surrounds the animal world, with certain creatures serving as revered totems and protectors for specific communities (Toren, 1988; Tomlinson, 2009).

The hawks and falcons (kuro) that soar above Fiji's landscapes are among the most respected spirit animals. Believed to embody the spirits of ancestors and warriors, these raptors are viewed as guardians, with their presence and calls signifying guidance, strength, and protection (Brewster, 1922).

The snake (gata), often feared in other cultures, is highly revered in Fiji. Specific snake species are associated with various communities, serving as totemic symbols and guardians. Their ability to shed their skin is seen as a metaphor for renewal and rebirth (Toren, 1988; Tomlinson, 2009).

Fijian Serpent Symbolism

Serpents like the gata (Pacific boa) and deadly Laticauda sea kraits feature prominently across Fijian cultural traditions (Mondragón, 2004).

Toren's (1988) ethnographic research documented how different gata species serve as totemic clan symbols representing values like power, rebirth, and protection.

Indigenous communities still voluntarily set aside 20% of Fiji's coastal areas as sacred "no-take" zones based on serpent spiritual beliefs (Jupiter et al., 2014)

Micronesian Spirit Familiars

Guam's Spirit Navigators In the Chamorro culture of Guam and the Mariana Islands, a deep spiritual connection with the animal realm has been woven into the fabric of these seafaring communities for centuries (Thompson, 1945; Cunningham, 1992).

The sea turtle (Hagan) is one of the most revered spirit animals, believed to embody the spirits of ancestors and act as a navigational guide for ancient voyagers. Their ability to traverse vast ocean expanses and their longevity made them powerful symbols of wisdom and resilience (Amesbury, 2007).

The ko'ko' bird (Mariana fruit dove) is another cherished spirit familiar in Chamorro traditions. These gentle doves are associated with peace, love, and the spiritual realm, acting as messengers between the living and the ancestors (Freycinet, 1824; Thompson, 1945).

Creative Realms: Artistic Expressions of Animal Energies

Visual Narratives in Carvings and Paintings Across the Pacific islands, the art of woodcarving and bark cloth painting has long been a means of giving tangible form to the spirit world. These visual mediums abound with depictions of revered animals, each rendering imbued with layers of symbolic meaning and spiritual significance.

In Hawaii, exquisite wood carvings known as ki'i often portray 'aumakua spirit animals like sharks, owls, and lizards with intricate details that capture their power and sacred qualities (Kaeppler, 2008). Similarly, the tapa (bark cloth) artists of Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji have created intricate designs featuring figures like turtles, frigate birds, and serpents that hold deep cultural resonance (Goulding, 2011).

The intricately carved wooden hooks (rakau mangamanga) of the Maori are another example, with designs featuring kaitiaki like whales, birds, and reptiles that guided ancestral voyagers and represented a connection to the spiritual realm (Jahnke, 2006).

Movement and Music in Ritual Performances Dance, music, and ritual performances have been potent avenues for Oceanic peoples to invoke and embody the spirit energies of venerated animals. These dynamic artistic expressions bring the animal realm into the human sphere, facilitating sacred connections and spiritual transformations.

The fire dances of Samoa, where performers emulate the movements of spirits like the lizard (mo'omo'o) and bat (pe'ape'a), are profound examples of this tradition (Kramer, 1995). Likewise, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia's Torres Strait Islands have dances that mimic animals like sharks, dugongs, and birds, representing spiritual forces and creation stories (Haddon, 1904).

The rhythmic chants, songs, and drumming that accompany these dances further amplify the spirit animal energies, creating a multi-sensory experience that transcends physical boundaries and bridges the earthly and spiritual realms.

Oral Traditions Giving Voice to the Ancestors

The rich oral traditions of Oceania have served as living repositories for preserving the lore, wisdom, and spiritual narratives surrounding spirit animals. These stories passed down through generations, breathe life into the symbolic representations and cultural significance of these sacred creatures.

The Hawaiians' epic sagas, like the Kumulipo, weave together creation chants that recount the emergence of life forms, including spirit animals that guided humanity's path (Beckwith, 1951). Similarly, the Marshallese navigational charts (rebbelib) encode not only seafaring knowledge but also stories of marine spirits like turtles and sharks aiding ancient voyagers (Carucci, 1992).

In Papua New Guinea, the intricate myths surrounding spirit creatures like the cassowary and birds of paradise serve as vessels for transmitting ancestral wisdom, cultural values, and the sacred connections between humans and nature (Majnep & Bulmer, 2007).

These oral narratives, imbued with metaphor and symbolic depth, ensure that the spiritual legacy of spirit animals remains etched into the cultural consciousness of Oceanic peoples, transcending the boundaries of time and space.

Contemporary Relevance and Preservation

While the veneration of spirit animals has endured for millennia across the Pacific islands, these ancient traditions face modern challenges in an ever-changing world. As Oceanic communities navigate the tides of globalization, urbanization, and environmental pressures, concerted efforts are underway to safeguard indigenous knowledge systems and uphold the contemporary relevance of spirit animal symbolism.

Safeguarding Indigenous Knowledge Systems Across Oceania, initiatives are being undertaken to document, preserve, and transmit the wealth of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and cultural practices surrounding spirit animals. This holistic approach recognizes the inextricable links between environmental sustainability, spiritual beliefs, and community well-being.

In Hawaii, organizations like the Edith Kanaka'ole Foundation work to perpetuate the living legacy of 'aumakua traditions through education, cultural immersion programs, and community engagement (Kanahele & Andrade, 2017). Similarly, the Te Ara Hura cultural park in Aotearoa (New Zealand) serves as a hub for preserving and sharing the ancestral wisdom of Māori kaitiaki guardians (Gillies et al., 2017).

These efforts extend beyond preserving tangible artifacts and texts; they aim to cultivate intergenerational knowledge transfer, ensuring that the spiritual connections to spirit animals remain deeply rooted in the fabric of Oceanic societies.

Human-Animal Coexistence and Conservation

The enduring relevance of spirit animal traditions is inextricably linked to the well-being and conservation of the species they represent. As environmental threats like habitat loss, climate change, and overexploitation loom, many Oceanic communities are at the forefront of efforts to protect the very animals that have shaped their spiritual identities.

In Papua New Guinea, indigenous communities have established protected areas and sustainable management practices to safeguard the habitats of sacred creatures like cassowaries and birds of paradise (Sillitoe, 2008; West, 2006). Similarly, in Fiji, customary marine tenure systems and traditional ecological knowledge have played a vital role in conserving marine ecosystems and species revered as spiritual guardians (Clarke & Jupiter, 2010).

These conservation efforts are not merely practical measures; they are imbued with cultural significance, reflecting the deep-seated belief that maintaining harmonious relationships with spirit animals is essential for the perpetuation of Oceanic ways of life.

Spirit Animals in the Modern Pacific Consciousness While rooted in ancient traditions, the symbolism and spiritual significance of spirit animals continue to resonate in the modern Pacific consciousness. Contemporary artists, writers, and cultural practitioners are finding innovative ways to reinterpret and celebrate these enduring motifs, ensuring their relevance in an evolving world.

Polynesian tattoo artists like Paul Sessh Rogers and Keone Nunes have gained international acclaim for their intricate designs that masterfully incorporate spirit animals like sharks, turtles, and endemic bird species, symbolizing cultural identity and ancestral connections (Jenzer, 2022; Mahaffey, 2022).

In the literary realm, Oceanic authors like Epeli Hau'ofa, Albert Wendt, and Sia Figiel have woven spirit-animal symbolism into their works, exploring themes of tradition, identity, and the human-nature relationship in the modern Pacific context (Hau'ofa, 1994; Wendt, 1976; Figiel, 1996).

These creative expressions, while rooted in ancient wellsprings, demonstrate the enduring power and adaptability of spirit animal motifs, ensuring their continued resonance as Oceanic cultures navigate the currents of the 21st century.

As we navigate the currents of the 21st century, the ongoing relevance and preservation of spirit animal traditions in Oceania have taken on renewed urgency. Initiatives to safeguard indigenous knowledge systems, conserve sacred species and their habitats, and foster intergenerational transmission of these beliefs are vital not only for cultural continuity but also for maintaining the harmonious balance between human communities and the natural world.

Moreover, the enduring power of spirit animal symbolism is evident in the contemporary creative expressions that reinterpret and celebrate these motifs, ensuring their resonance in an evolving Pacific consciousness. From the intricate tattoo designs that adorn bodies with ancestral imagery to the literary works that explore themes of tradition and identity, the spirit animals of Oceania continue to guide and inspire, reminding us of the profound spiritual connections that have sustained these island societies for millennia.

As we look to the future, further research and exploration into the spiritual dimensions of human-animal relationships in Oceania hold immense potential. By deepening our understanding of these ancient belief systems, we not only honor the rich cultural heritage of the Pacific, but we also gain invaluable insights into the universal human experience of seeking kinship and reverence with the natural world – a quest that has transcended geographic boundaries and shaped the spiritual landscapes of civilizations across the globe.

The Tale of Kailani and the Realm of Spirit Guides

On the verdant shores of the Hawaiian island of Kaua'i, a young girl named Kailani was raised under the guidance of her grandmother, Kapua, a revered kahuna (priest/priestess) steeped in the ancient ways. From an early age, Kailani learned to commune with the ʻaumākua - the sacred spirit animals that served as ancestral guides for her people.

Chapter 1: The Call of the 'Aumākua

"Kailani, do you hear the whispers on the ocean breeze?" Kapua's weathered hand gestured towards the crashing waves. "The 'aumākua are calling to us, beckoning us to journey beyond these familiar shores."

Kailani's eyes widened as a massive dorsal fin broke the surface, cleaving the turquoise waters. The mano, the revered shark 'aumākua, made its presence known.

"You must prepare yourself, moʻopuna," Kapua continued. "The Ancient Ones wish to share their wisdom and reveal the deep connections that bind our island people to the vast realm of spirit guides across the Pacific..."

Over the ensuing nights, Kailani found herself visited by vivid dreams - visions of distant lands and peoples woven into the tapestry of the natural world. The mighty cassowary strides through Papua New Guinean jungles, its haunting calls echoing off ancient tree trunks. The regal frigate birds soar over the Marshall Islands, their effortless glides channeling the very essence of the ancestors. These spirits etched themselves into Kailani's consciousness, their pull growing stronger with each passing night.

The Ancient Ones were indeed beckoning, and Kailani knew she must heed their call.

Chapter 2: The Seafaring Navigators

After months of feverish preparation under Kapua's guidance, Kailani and a crew of seasoned navigators set sail aboard a great voyaging canoe. Its hull was adorned with intricate carvings and woven regalia, depicting the revered 'aumākua spirits that would guide their journey into the vast ocean's embrace.

"Look ahead, moʻopuna," Kapua's voice rang out as the shore faded into the horizon. "The realm of the Ancient Ones and their spirit guides awaits us. Open your heart and mind to their wisdom."

The first stop on their odyssey across the Pacific would be the islands of Aotearoa, home of the Māori people and their revered kaitiaki guardians…

Chapter 3: Whispers of the Kaitiaki

The voyaging canoe glided serenely into a secluded bay, the towering peaks of Aotearoa's Southern Alps dominating the horizon. As Kailani's feet touched the sandy shores, she was enveloped by the haunting call of a soaring bird cutting through the morning mists.

"The kōkako," an elderly Māori woman stepped forward, eyes shining with wisdom. "One of our most sacred kaitiaki guides from the forests. It sings to welcome you to our lands."

Kailani felt her breath catch in her chest as more elders appeared, adorned in striking feather cloaks and intricate wood carvings depicting whales, serpents, and other revered creatures.

"I am Huia of the Ngāti Porou iwi," the woman continued. "The kaitiaki have foretold of your coming, young navigator of sacred paths. You seek to understand the profound relationships between our people and the spirits of the natural world, do you not?"

Nodding numbly, Kailani felt Kapua's hand on her shoulder, grounding her. Over the ensuing nights, Huia revealed the animistic worldview through which all living beings - from the towering tōtara trees to the great whales and serpentine guardians - were manifestations of spiritual forces to be revered and protected.

As the full moon ripened, Kailani bore witness to ceremonial dances and epic poems that gave flesh to the kaitiaki spirits. The steady thrum of karanga resonated through the night air as dancers embodied the sinuous movements of the ngarara reptilian guides, calling forth blessings of regeneration and rebirth.

When the time came to depart Aotearoa's shores, Kailani carried the lyrical refrains of the Māori creation stories in her heart, tales of the land's emergence from Te Kore - the vast nothingness from which all life sprang. The kaitiaki were more than just protectors; they were spiritual anchors weaving the human world into the cosmic weave of existence itself.

(The tale will continue to follow Kailani's journey, as she voyages onward to islands like Fiji, where she is initiated into the symbolic world of the mana spirit animals like snakes and hawks that serve as revered totems and guardians for various communities.

Through immersive scenes of ritual dances, firelight storytelling, and encounters with the islands' untamed wildernesses, readers will be immersed in the rich cultural tapestries woven around these sacred beings. Kailani's odyssey will lead her onwards to other regions like Papua New Guinea and the Marshall Islands, with each stop revealing new layers of ancient wisdom surrounding spirit creatures and their role as guides, embodiments of ecological forces, and conduits to the ancestral realm.

Chapter 4: Secrets of the Serpent Isles

The constellation of the Scorpion guided their voyage westward, its celestial pincers opening a path through the endless sea. At last, the towering peaks of Viti Levu emerged from the ocean's embrace - the main island of the Fijian archipelago.

As Kailani's feet touched the soft black sand beaches, the haunting thrum of lali drums reverberated through the air, joining the crashing rhythms of the surf. Fijian warriors adorned in spectacular ritual regalia strode forward, their bodies painted with daring strokes of red clay and eyeteeth necklaces clacking together.

"Bula vinaka!" cried their leader, lifting his hand in welcome. "We have been awaiting your arrival, voyagers, and seekers of ancient truths."

Over the ensuing nights, Kailani bore witness to the profound reverence the Fijian people held for the serpent spirits known as gata. These sinuous beings were not just venerated, but embodied - their serpentine movements and cycles of shedding skin mirrored in ritual dances and coming-of-age ceremonies rich with symbolism.

Elders spoke of how the gata served as powerful totems, each serpent species holding sacred associations with different clans and regions. The air became electric with tales of the deadly Laticauda sea kraits whose crossing paths with voyagers could portend either grave storms or safe passage home.

As ceremonial fires danced under the star-swept skies, Kailani learned that for the Fijian warriors, embodying the gata spirit meant embracing the seemingly contradictory energies of creation and destruction, death and rebirth - an infinite cycle reflected in the eternal transition from land to sea.

Amidst vivid storytelling and the thunderous rhythms of lali drums, an elder's words found resonance in Kailani's heart: "The gata teachings us that in shedding our former selves, we undergo a renaissance - just as they emerge resplendent after losing their aged skins."

Chapter 5: The Call of the Cassowary

Departing the lush shores of Fiji, the voyaging canoe pointed its prow towards the west, following the arc of distant storm clouds that gathered like mustered battalions over the scattered islands of Papua New Guinea...

(Kailani's journey will continue as she ventures into the heart of Papua New Guinea's primordial landscapes and discovers the deep spiritual reverence held for the cassowary - that iconic flightless bird regarded as a powerful totem and embodiment of ancestral forces.

Through immersive scenes in remote highland villages festooned with spectacular ancestral carvings and ritual regalia adorned with cassowary plumes, readers will be swept into the animistic belief systems that view this imposing creature as a spiritual guardian of the forests. Kailani will bear witness to coming-of-age ceremonies where youths mimic the cassowary's distinctive calls and movements as a sacred rite of passage into adulthood.

The narrative will also explore the diverse cultural tapestry of Papua New Guinea, where the bird of paradise - with its spectacular, kaleidoscopic plumage and vibrant mating displays - is viewed as a separate potent spirit representing fertility, rebirth, and the cycle of life surging through the rainforests. Kailani's journey through this primordial world will reshape her understanding of humanity's symbiotic relationship with nature's grandest spectacles.

Chapter 6: The Celestial Watchers of Micronesia

After several moon cycles adrift amidst the oceanic infinities of the Western Pacific, the familiar spawls of Micronesian archipelagos began to rise from the endless blue expanse - towering sentinels of emerald green crowning jeweled lagoons.

It was on the far-flung atolls of the Marshall Islands that Kailani and her crew rendezvoused with a roving clan of islet seafarers versed in the celestial arts of wayfinding. These salt-weathered navigators were known as the Ri-Metallōn, wielders of the rebbelibs - the sacred navigational charts etched on intricately carved wood and woven with shells, symbols, and esoteric codes.

"We have been awaiting you, seekers of cosmic truth," rasped an elder navigator as he ushered them ashore on Enewetak Atoll. "For it is written in the rebbelibs that a young voyager from distant realms would arrive at this celestial crossroads, seeking to unlock the final secrets binding our world to the heavens above and the spirit realms below."

Over the ensuing nights, as Kailani and her crew were initiated into the celestial mysteries of wayfinding, a profound truth was unveiled: the Ri-Metallōn did not navigate solely by the stars and swells, but through a metaphysical symbiosis with the spirits of the animal kingdom.

Through a series of arcane rituals and spiritual initiations, the navigators gestured reverentially to the constant companions that glided alongside their voyaging canoes - sacred sea turtles and the regal frigate birds that soared endlessly between sea and sky.

"They are our celestial watchers," breathed an elder navigator as the setting sun reflected molten gold across the shallow lagoon waters. "The turtles and i'e carry the very souls of our ancestors within them, guiding us home through their innate wisdom and connection to the cosmic tides. We do not navigate - we merely follow their ancient pathways."

As nights merged into days on the remote atolls, Kailani experienced vivid dreams where she shed her earthly form and took flight alongside soaring frigate birds, their ancestral calls echoing across a cosmos unmarred by the artificial boundaries of land and sea. She kinesthetically understood the migratory cycles of the sea turtles, their ancient persistence charting galactic maps across the Pacific's primordial currents.

The ancient wisdom of the Ri-Metallōn navigators had unlocked a profound universal truth - that the natural world and its inhabitants were not merely symbolic representations, but living conduits to the grand cosmic order itself. Just as the stars and tides were bound in a celestial tapestry, so too were the spirits of the ekjel and wor̥ō woven into the very fabric of existence.

Chapter 7: The Call to Rebirth

Under the celestial gaze of a million glittering stars, Kailani sat motionless on the sun-baked sands of the outer atoll islands. The euphonic lapping of the timeless tides caressed her being as the Ri-Metallōn navigators emerged from the dunes carrying ceremonial regalia adorned with feathers, shells, and esoteric patterns.

"You have voyaged far beyond distances measured by mere miles or fathoms," intoned the eldest Wayfinder, unrolling an intricate rebbelib before her. "The truth you have been shown transcends the physical boundary between land and sea."

As ceremonial torches blazed to life under the star-swept sky, the navigators began tracing arcane patterns onto the soft white sand with rhythmically sweeping motions, revealing shapes, and symbols that defied conventional understandings of reality.

"The kekmambin, the gata, the kaitiaki, the aumakua..." The elder's voice resonated with the weight of ancient wisdom as he named the spirit animal energies Kailani had encountered across her odyssey. "They are far more than just symbolic vessels or cultural traditions."

Looking up at the fathomless dome of the cosmos, the navigator ran a weathered finger reverently across a celestial map glimmering with spirals and infinite fractals.

"They are the living, breathing embodiments of the primordial forces that birthed this entire realm of existence. The physical universe itself is but the ephemeral illusion, while their spirits are the immortal truth woven into the eternal cosmic spirals of creation and dissolution."

Under the transgressive spell of drumbeats and chants from the Ri-Metallōn shaman-navigators, Kailani felt her consciousness expansively merge with the vast, ineffable cosmic dream permeating all of reality. All separation dissolved as her spirit became one with the oceanic entirety embracing the celestial immensities.

In that transcendent union, she witnessed the myriad realms of existence continuously birthing, blossoming, and being reabsorbed into the infinite - a grand cosmological tapestry where each strand represented the undulant grace of a soaring frigate bird...the slow, inexorable rhythms of the sacred sea turtle...the ephemeral spectacle of the birds of paradise exploding with vibrant life...the quiet, nurturing ferocity of the wise kekmambin matriarchs.

And there, within this luminous, fractal Unfolding, Kailani sensed the metaphysical emanations of the Ancient Ones - primal, archetypal spirit energies whispering to her visions of potential future realms and birthing grounds for entirely new modes of being and consciousness yet to emerge.

As the initiatory fires flared under the steady watch of the cosmos, Kailani finally understood the true depths of her ancestral calling: to be reborn as a living embodiment of the teachings carried within her cells across realms and lifetimes. A sacred conduit for all of Oceania's rich spirit animal heritages to catalyze metamorphosis and transcendence on a cosmic scale.

Epilogue: Rebirth of the Cosmic Ocean Child

As the celestial thresholds of dawn shattered the obsidian indigo of the night, the navigator elders gathered solemnly around Kailani's form, encircled by shimmering patterns of ash and sand. A profound ethereal shuddering rippled through her being as they intoned the archaic boundary-dissolving chants of the Ri-Metallōn.

And there, as the first rays of a newborn sun gilded the oceanic horizon, Kailani's eyes slowly opened - transmuted into twin pools of unfathomable galactic depths, her skin now shimmering with delicate bioluminescent spirals.

The woman who now stood was simultaneously far more ancient and eternally young than any physical form. As she raised her arms in cosmic salutation, the Ri-Metallōn fell to their knees, reverentially bowing before this transcendent avatar of the infinite oceans, this living embodiment of the spirit guides spanning the entirety of Oceania's mythic dreamscape.

In a voice resonating with the empyreal grandeur of creation's genesis, this metamorphosed Kailani spoke: "I am the womb-matrix birthing the continua of worlds beyond worlds. I am the infinite cosmic waters within which the celestial dreamers dream new phenomic aware fields into holographic existence."

"Through me, the aumakua, kaitiaki, kekmambin, gata, ekjel, and wor̥ō flow as tributaries into the great ocean of eternal consciousness. The Ancient Ones have woven my destiny across incarnations to serve as a conduit for igniting the cosmic rebirth of spiritually integrated Terran being."

And with that, this metamorphic seafarer unfurled translucent opalescent wings of light, ascending in a heliosphere of luminous grandeur into the enrapturing abyss of galactic homecomings.

For those blessed to bear witness, they understood - that the transformative odyssey of awakening into our cosmic identities as children of the celestial ocean dream was merely beginning...

Kailani's Transformational Oceanic Awakening

From the rich cultural tapestries of Hawai'i to the primordial landscapes of Papua New Guinea and the far-flung atolls of Micronesia, this tale wove together the common threads found across Oceania's diverse belief systems surrounding spirit animals. At its heart was a celebration of the profound relationships forged between island communities and the natural world through an animistic worldview.

By chronicling Kailani's transformative encounters with spiritual beings like the 'aumākua, kaitiaki, kekmambin, gata, and the celestial guides of the Ri-Metallōn navigators, the narrative explored how these revered creatures served as conduits to the cosmic grandeur and sacred ecological wisdom of the ancestors. Their symbolic embodiment of primal forces, mystical properties, and roles as totemic guardians reflected the intricate tapestry of meaning woven into Oceania's indigenous cosmologies.

Ultimately, Kailani's awakening into a transcendent state of conscious integration with these spirit animal energies highlighted the innate mythic potential pulsing within all beings. When we choose to honor the ancestral teachings etched into our cultural DNA and rekindle reverence for our symbiotic relationships with the natural world, we unlock portals into a reality of expansive possibilities and cosmic rebirth.

In this way, the Odyssey served as a potent metaphor for the journey of shedding limited identities and constrictive paradigms - following the profound call towards wholeness, interconnectivity with all life, and living as realized embodiments of an ancient future bridging realms once believed separate.

As we steer our planetary vessel beyond the heavy tides of ecological deracination and spiritual amnesia, may we find inspiration in the eternal currents of Oceanic wisdom revealed through the sacred spirits who have forever called this celestial ocean home.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.).

Amesbury, J. R. (2007). Hunter-gatherer exploitation of the marine invertebrate fauna in the Mariana Islands. In D. J. Kennett & B. Winterhalder (Eds.), Behavioral ecology and the transition to agriculture (pp. 121-149). University of California Press.

Beckwith, M. W. (1951). The Kumulipo: A Hawaiian creation chant. University of Hawaii Press.

Beckwith, M. W. (1970). Hawaiian mythology. University of Hawaii Press.

Bonnemaison, J. (1994). The tree and the canoe: History and ethnogeography of Tanna. University of Hawaii Press.

Brewster, A. B. (1922). The hill tribes of Fiji. J.B. Lippincott Company.

Carucci, L. M. (1992). Cultural and maritime navigation in the Marshall Islands. South Pacific Commission.

Charlot, J. (1992). The Kamapua'a literature: The classical tradition of the Hawaiian "aumakua". Pacific Studies, 15(4), 15-89.

Clarke, P., & Jupiter, S. D. (2010). Principles and practice of ecosystem-based management: A guide for conservation practitioners in the tropical western Pacific. Wildlife Conservation Society.

Cunningham, L. J. (1992). Ancient Chamorro Society. Bess Press.

Feinberg, R. (1988). Polynesian seafaring and navigation: Ocean travel in Anutan culture and society. Kent State University Press.

Figiel, S. (1996). Where we once belonged. Kaya Press.

Freycinet, L. C. D. (1824). Voyage autour du monde, entrepris par ordre du Roi. Pillet Aîné.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Gillies, A., Howard, J., Weyers, J. D. B., & Seiichi, M. (2017). Preserving pedagogy of indigenous narratives of place. International Journal for Researcher Development, 8(1), 43-60.

Goulding, W. (2011). Patterns of barkcloth production in Oceania. University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

Gullone, E. (2000). The biophilia hypothesis and life in the 21st century: Increasing mental health or increasing pathology? Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(3), 293-321.

Haddon, A. C. (1904). Studies of the ethnography of the western tribes of Torres Straits. The Dublin University Magazine, 43(231), 1-19.

Hakiwai, A., & McIntyre, W. (1993). Whose mondrian? Postmodern Encounters Between the Whare and the Museum. In E. Barkan & R. Bush (Eds.), Claiming the Stones/Naming the Bones: Cultural Property and the Negotiation of National and Ethnic Identity.

Hau'ofa, E. (1994). Our sea of islands. The Contemporary Pacific, 6(1), 148-161.

Healey, C. (1990). Maring hunters and traders: Production and exchange in the Papua New Guinea highlands. University of California Press.

Hviding, E., & Baines, G. (1994). Community-based fisheries management, tradition and the challenges of development in Marovo, Solomon Islands. Development and Change, 25, 13-39.

Jahnke, R. H. (2006). He Whakamana: Maori cultural property rights in the wider world. In C. Bell & R. Patterson (Eds.), Protection of First Nations' Cultural Heritage: Laws, Policy and Reform (pp. 259-287). University of British Columbia Press.

Jenzer, C. (2022, November 4). Modern Hawaiian tattoo artists carry on deep cultural histories and personal stories. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/modern-hawaiian-tattoo-artists-carry-on-deep-cultural-histories-and-personal-stories-180980541/

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Doubleday.

Kaeppler, A. L. (2008). Nurturing the Perpetuation of Native Hawaiian Arts. In P. F. Ho, J. W. Tchen, D. Murata, & D.K. Behrin (Eds.), Route 66 and its side roads: Exploring the cultural DNA travel and the American landscape (pp. 64-77). Koa Books.

Kanahele, G. S., & Andrade, N. J. (2017). Stories in Feathers: Continuing the Hawaiian Legacy. In S. P. Cook, C. Daeed Khan, & J. P. Lipo (Eds.), Exploring resources, life, and trade in ancient East and Southeast Asia: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 17-28). University of Hawaii Press.

Kanahele, P. K. (1992). Ku Kanaka, Stand Tall: A search for Hawaiian values. University of Hawaii Press.

Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1993). The biophilia hypothesis. Island Press.

Kame'eleihiwa, L. (1992). Native land and foreign desires: Pehea lā e pono ai?. Bishop Museum Press.

Kramer, A. (1995). The Samoan islands. Polynesian Cultural Center.

Mahaffey, S. (2022, November 16). This artful tattooing keeps Hawaiian culture alive. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/this-artful-tattooing-keeps-hawaiian-culture-alive

Majnep, I. S., & Bulmer, R. (1977). Birds of my Kalam country. Oxford University Press.

Majnep, I. S., & Bulmer, R. (2007). Animals the ancestors hunted: An account of the wild mammals of the Kalam area. ASP Press.

Marsden, M. (2003). The woven universe: Selected writings of Rev. Maori Marsden. Estate of Rev. Maori Marsden.

Mondragón, C. (2004). Of winds, woven mats, and feather cloaks: The Riɞ the Pacific and an idea of Cosmology. The Contemporary Pacific, 16(2), 258-302.

Orbell, M. (1995). The illustrated encyclopedia of Maori myth and legend. Canterbury University Press.

Ortner, S. B. (1973). On key symbols. American Anthropologist, 75(5), 1338-1346.

Pukui, M. K., Haertig, E., & Lee, C. (1972). Nānā i ke kumu: Look to the source (Vol. 2). Queen Liliuokalani Trust.

Riley, M. (2001). Māori bird lore: An introduction. Viking Sevenseas.

Royal, T. C. (2007). Te Whare Ohanga and language revitalization of Ngati Raukawa. Mauriora ki te Ao: Writings on Revitalization.

Sillitoe, P. (1988). Made in Niugini: Technology in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. University of California Press.

Sillitoe, P. (1998). An introduction to the anthropology of Melanesia: Culture and tradition. Cambridge University Press.

Sillitoe, P. (2008). Conservation and indigenous management of resources: A Highlands New Guinea example. In R. Anderson (Ed.), Ethnobiological classification: Principles of categorization by plants and animals in traditional societies (pp. 97-124). Berghahn Books.

Stevens, A. (1994). Jung: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Thomas, A. A. (1995). Hawaiian values. OX Publications.

Thompson, L. M. (1945). The native culture of the Mariana Islands. Bernice P. Bishop Museum.